Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp & Mario Casilli/Gene Trindl/mptvimages.com

In Miranda, the Warren court had ruled that statements made by a suspect during the course of a custodial interrogation by the police could not be used in court unless the suspect had been warned of his or her right to remain silent and to have counsel present during the questioning.

In 1969, Rehnquist, then an assistant U.S. attorney general during the Nixon administration, laid bare his views on the Warren court and its jurisprudence regarding criminal defendants.

“There is reason to believe that the Supreme Court has failed to hold true the balance between the right of society to convict the guilty and the obligation of society to safeguard the accused,” he wrote. Rehnquist was especially critical of Miranda, writing that “the court is now committed to the proposition that relevant, competent, uncoerced statements of the defendant will not be admissible at his trial unless an elaborate set of warnings be given, which is very likely to have the effect of preventing a defendant from making any statement at all.”

During his tenure on the U.S. Supreme Court, Rehnquist authored or joined numerous opinions carving out exceptions to the Miranda doctrine while limiting the scope of the original 1966 ruling. Most notably, he wrote the majority opinion in the 1984 case of New York v. Quarles, which found that suspects need not be Mirandized when there was a threat to public safety.

So when Dickerson v. United States, a case to determine the legality of an act of Congress overturning Miranda, hit the docket in 2000, one could just imagine Rehnquist licking his lips.

As an assistant U.S. attorney general during the Nixon administration, William Rehnquist was openly critical of the liberal Warren court’s 1966 decision in Miranda. In 2000, however, when the U.S. Supreme Court considered overturning the landmark decision in Dickerson v. United States, Chief Justice Rehnquist instead reaffirmed it, writing the opinion himself. Photographs by AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi; SHUTTERSTOCK

Then Rehnquist went the other way. He reaffirmed the Miranda doctrine.

While his opinion focused more on whether Congress can overrule a Supreme Court decision that deals with constitutional rights, it was this line from Rehnquist’s opinion that got the most attention:

“Miranda has become embedded in routine police practice to the point where the warnings have become part of our national culture,” Rehnquist wrote for a seven-justice majority. “It announced a constitutional rule that Congress may not supersede legislatively.”

IT’S EVERYWHERE

Thanks to all those TV shows and movies where the police read suspects their rights, the Miranda warning has become so ubiquitous that almost everyone can recite the various warnings by heart. In fact, the warnings have become such an accepted pop culture trope that fictional depictions have to show them if they want to be taken seriously, while comedies can get a lot of laughs by changing the words and playing with the audience’s expectations.

“It’s like doing a medical show and the doctors have to wear white coats to make it look real,” says Paul Bergman, a professor of law emeritus at UCLA School of Law. “Miranda warnings have become the way to demonstrate reality. It’s hard to imagine police arresting people these days without giving them the warnings.”

Miranda warnings have become so intertwined with police procedure, even foreign television shows and movies utilize them.

“Russian TV shows have Russian cops giving the Russian equivalent of the warning even though there’s no such requirement in Russian law,” says Tracey Maclin, a professor at Boston University School of Law. “That shows how Miranda has really outgrown and surpassed its original intent.”

In pop culture, the warning is a central, bedrock legal principle that remains uncontroverted and undiluted by time. But that stands in stark contrast to its actual status.

A widely misunderstood decision when it was handed down, Miranda remains controversial even after 50 years as controlling precedent. To many it represents the “legal technicality” that lets bad people roam free. Legal experts and law enforcement personnel continue to argue about what Miranda actually means and what police officers must do before they can interrogate a suspect.

There is also an enduring debate over whether Miranda has been the procedural impediment it was decried to be when Warren and his majority handed down their decision.

That’s assuming Miranda even exists anymore and, if it does, whether it is even necessary.

JUST ANOTHER CONTROVERSY

Warren and his fellow justices were no strangers to controversy. “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards and bumper stickers were common throughout the South, where seg-regated public schools became illegal thanks to Brown v. Board of Education and other rulings. Warren and his court earned the ire of conservatives everywhere by taking a broad view of free speech, reproductive rights and due process while vigilantly maintaining a clear separation of church and state.

But it was the Warren court’s decisions in favor of expanded rights for the accused that angered large swaths of the country. Richard Nixon seemed to spend more time during the 1968 presidential campaign attacking Warren and his pro-defendant court than going after his opponents in the race. And it was Warren’s decision in Miranda that may be his most controversial, if not most famous, opinion.

“Miranda really angered a lot of people,” says Maclin. “One of the big reasons was the way police reacted to it. They essentially said: ‘We won’t be able to solve any more crimes, and we’ll have murderers and rapists running free.’ “

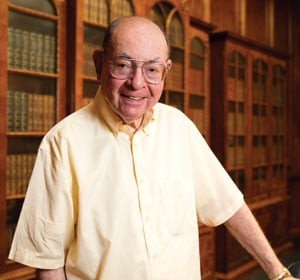

Yale Kamisar, a guest lecturer and retired law professor at the University of Michigan Law School who is often referred to as the “father of Miranda” because his research and scholarship on custodial interrogations was widely cited in Warren’s majority opinion, remembers being taken aback by the outcry against the decision.

Chief Justice Earl Warren (bottom row, center) and his Warren court were a major topic of Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign. AP Photo.

“It was scary how strong the negative reaction to Miranda was,” Kamisar recalls. “I went to an ABA event in Canada right after the decision came down, and there were state chief justices circulating petitions to try and get rid of it.”

Kamisar also remembers giving a talk about the decision, and attendees were openly scowling and muttering things at him while he was at the podium. “I looked around the room for some allies,” Kamisar says. “I found some, but their heads were down and they refused to make eye contact with me.”

TV TRUTH

In some ways, television blunted some of the criticism and allayed fears that police departments would have to start retrofitting their jail cells with revolving doors.

For one thing, the cops had to get their Miranda-related verbiage from somewhere, and the decision itself was of no help. One of the biggest misconceptions is that it created the now-ubiquitous warnings. The Miranda decision only mandated that warnings be issued to suspects in custody so that they are made aware of their right against self-incrimination and their right to counsel. The actual wording or phrasing was left up to the various law enforcement agencies.

But letting individual police departments come up with their own verbal warnings could be an invitation to chaos and years of follow-up litigation. Hoping to nip that in the bud, California’s attorney general at the time, Thomas Lynch, called for a statewide conference of law enforcement personnel soon after Miranda was handed down to coordinate the state’s implementation of the ruling. Lynch wanted a simple, easy-to-remember set of written warnings that every police officer in the state could use, and he called on Deputy State Attorney General Doris Maier and Nevada County District Attorney Harold Berliner to do it.

“Doris and I met for a couple of hours in Sacramento,” Berliner told the Sacramento Bee in 2000, 10 years before his death. “We sat down and tried to find practical words to express the court’s notion in language simple enough for an ordinary suspect to understand.”

Berliner may have been an attorney, but his first love was publishing. He owned a printing press and, while he may not have been a professional wordsmith, he knew what worked and what didn’t. He and Maier crafted a short, succinct set of warnings that were easy to remember and had almost a sing-song quality to them.

“It’s almost like a mantra—like what you see at 12-step programs,” Bergman says. “There’s a staccato quality to it that gives it a sort of rhythm. It’s concise, terse and easy to remember.” Berliner used his press to print laminated, wallet-size cards so that every police officer in the state would have a copy of the warnings handy when patrolling and making arrests.

Berliner told the newspaper he believed he and Maier were the first to write formal Miranda warnings and distribute them on a large-scale basis. Berliner believed that head start allowed his version of the warnings to become the standard that almost everyone continues to follow.

“It was scary how strong the negative reaction to Miranda was.” —Yale Kamisar. Photograph by Wayne Slezak.

“Harold would say that when Tom Lynch asked him and Doris to draft the Miranda warning, he had no idea that it would become such an important part of the criminal justice system,” says Ragan Powers, a partner at Davis Wright Tremaine in Seattle and Berliner’s son-in-law.

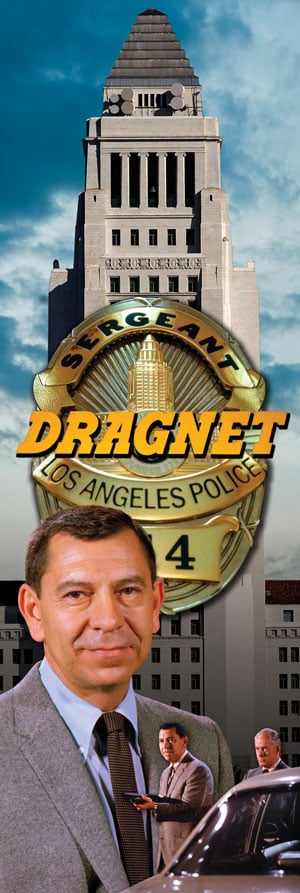

Berliner also had Hollywood star Jack Webb to thank. Berliner’s Miranda card caught the attention of Webb, producer and star of TV’s Dragnet, which began on radio in 1949. Webb was something of a perfectionist and wanted his show to be as realistic as possible. Knowing that police officers in the state were using the card as a part of the job, Webb decided to include the warnings as a trope on the show. When the TV series was revived in 1967, Miranda warnings became a regular feature of the show’s scripts, as well as a catchphrase of sorts for Webb’s deadpan “just-the-facts-ma’am” character, Detective Joe Friday.

For viewers, Webb’s monotonous yet rhythmic cadence helped drill the warnings into their consciousness, while the regularity with which he delivered them to the designated perp-of-the-week legitimized Miranda as a routine part of police procedure.

Christopher Stone, president of the Open Society Foundations, a government-accountability advocacy group, says television shows like Dragnet played an important part in saving Miranda and refuting its many critics. Instead, Dragnet showed viewers that good cops would always be able to solve crimes even with Miranda, and that police could still interrogate suspects even after reading them their rights.

“When it comes to pop culture, Miranda is strong and gets stronger every year,” Stone says. “It really was rescued by shows like Dragnet that taught Americans and people all over the world something that wasn’t legally true: That cops have to give you warnings when they arrest you, and they have to give you a lawyer.”

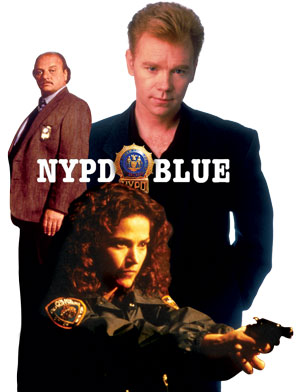

Subsequent cop shows, including Adam-12, Hill Street Blues, Law & Order and NYPD Blue, only served to reinforce the idea that Miranda was all part of routine police procedure. NYPD Blue, in particular, was known for being very accurate when it came to issues surrounding the Miranda warnings.

“There were at least a couple of episodes where they made the point of Mirandizing someone who could only speak Spanish,” says Keith Rowley, a law professor at the William S. Boyd School of Law at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. “That’s because reading someone a warning in English when they don’t understand it is like not reading it at all. Courts have said something to the effect that if you arrest someone who is a Spanish speaker, then you have to give them their rights in Spanish.”

TV UNTRUTH

Of course, not all shows or movies are meant to be as accurate as possible.

TV producer and actor Jack Webb is credited with taking the Miranda warning mainstream on Dragnet. Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp & Mario Casilli/Gene Trindl/mptvimages.com

“It almost seems to be mandatory in every TV show or movie to have police read a suspect his or her rights—even at times when no reasonable police officer would do it,” says Devallis Rutledge, special counsel for the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office. Police officers usually wait until they’re back at the precinct and ready to begin interrogation before reading the rights. “It causes our jury pool to believe that’s what really happens. So when it doesn’t happen that way, they think there’s a problem.”

Rutledge is clearly not a fan of Miranda. He thinks law enforcement has never recovered from that fateful day when Chief Justice Warren handed down his majority opinion, and he points to crime clearance rates from the FBI to back up his argument.

“In the 1950s, police officers cleared 63 percent of violent crimes that were reported,” Rutledge states. “After Miranda was handed down in 1966, that rate took a nosedive over the next four years down to 45 percent, and it has never recovered. There’s nothing else that happened in 1966 that explains this.”

But perhaps no one in America believes Miranda has harmed law enforcement as much as Paul Cassell. The University of Utah law professor was one of the attorneys who argued the Dickerson case before the Rehnquist court, and he was bitterly disappointed at the outcome.

Cassell was appointed to argue in favor of the congressional statute at issue (18 U.S.C. S 3501) after the U.S. Department of Justice took the viewpoint that the statute was unconstitutional and refused to defend it.

Reflecting back on Dickerson after 16 years, Cassell believes Rehnquist’s line about Miranda being immersed in our popular culture has gotten too much attention, and he maintains that the case really wasn’t about that. “My brief made clear that federal agencies would continue to give Miranda warnings no matter what happened because it demonstrates the voluntariness of the statement,” Cassell says. “Maybe it showed the court wasn’t seriously invested in looking at doctrinal issues relating to Miranda.”

Instead, Cassell continues to emphasize that Miranda has “handcuffed the cops over the last 50 years.” It was Cassell’s research that produced the figures Rutledge cited concerning clearance rates. Cassell has also argued that confession rates fell after 1966 and pointed the finger squarely at Miranda.

“Popular culture makes people think it’s just reading words off a card, but there are lots of procedural issues that impede cops,” says Cassell. “There’s no question that Miranda has damaged law enforcement.”

It may not be a question for Cassell, but it is for many others in academia and even law enforcement. Stephen Schulhofer, a professor at New York University School of Law, has been debating Cassell for years about the effects of Miranda. Schulhofer has found fault with Cassell’s data, while claiming that the Utah professor has overstated his conclusions. In 1996, Schulhofer re-examined Cassell’s study of conviction rates. Schulhofer took issue with Cassell’s methodology, specifically faulting him for ignoring a Los Angeles study that showed a dramatic increase in confessions because Cassell didn’t think it was possible. Instead, Schulhofer found there had been a decrease of less than 1 percent in overall conviction rates since Miranda, a negligible result.

“I think the evidence is overwhelming that Miranda has not handcuffed law enforcement,” Schulhofer says.

In fact, Schulhofer argues the Miranda ruling isn’t really about the warnings. “The warnings are important,” he says. “But the heart and soul of Miranda is the ‘cut-off rule.’ If the suspect indicates at any time he no longer wants to answer questions, then all questioning must cease, period. Many police departments gave warnings before Miranda, but once they started questioning, they could go as long as they wanted to.”

“When it comes to pop culture, Miranda is strong and gets stronger every year.” —Christopher Stone. Photograph by David Hills.

He says that before Miranda it was common, and even expected, for police to put suspects in the interrogation room and then question them for hours at a time.

RIGHTS NOT USED

Even with the cut-off rule, an overwhelming number of suspects simply don’t invoke their rights. Studies have shown that more than 80 percent of suspects waive their Miranda rights and voluntarily speak to police.

Richard Leo, a law professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law, notes that most people’s natural inclination is to talk.

“We are socialized to believe that if the authorities speak to us, we have to answer them, and that it looks like you have something to hide if you don’t,” he says. “The expectation of an interrogation is that you will cooperate, and there’s a lot of implicit, subtle pressure to do so.”

Leo also points out that police are very good at de-emphasizing the Miranda warnings, making them seem like no big deal and directing suspects to sign the waiver form. In this instance, Leo argues, pop culture has also played a role.

“People think they know about Miranda because they see it on TV,” Leo says. “To the extent that it educates people as to their rights, then it’s a good thing. To the extent that it desensitizes people to the real meaning of Miranda so they mindlessly waive their rights, then it’s not a good thing.”

Cops on TV are also very good at making suspects think that they can make everything go away, and that if a suspect doesn’t speak up the cops can’t help him or her. “You see that all the time on a show like Law & Order,” Leo says. “A suspect gets tricked into thinking the cops are there to help and ends up confessing to everything.”

William Fitzpatrick, the district attorney for Onondaga County in New York, has found that most suspects think they can talk their way out of their predicament.

NYPD Blue was known for being exceptionally accurate regarding Miranda, even having arrestees’ rights read to them in their native language. Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp & Mario Casilli/Gene Trindl/mptvimages.com

“Many times, it works to their detriment because they tell falsehoods and lies, and that points to consciousness of guilt,” says Fitzpatrick. He says that, overall, Miranda has not made things more difficult for law enforcement, pointing out that “if you follow Miranda and make sure everything is done right, then you get more guilty pleas.”

Indeed, Miranda can actually serve to legitimize police tactics and serve as a stamp of approval for the confessions they elicit. Yale law professor Steven Duke says Miranda has virtually eliminated inquiries as to the voluntariness of a confession.

“Before Miranda, the Supreme Court was preoccupied with the voluntariness of a confession,” Duke says. “Nowadays, almost no court will exclude a confession unless there was strong proof that the cops threatened or used physical harm.”

Despite that, some continue to argue Miranda should be wiped off the books. Cassell, for one, maintains that increased use of videotaping interrogations would provide suspects with the same level of protection as Miranda.

“People assume all interrogations are recorded, but that’s not true—a large number of police departments do not” use video, he says. “The Miranda doctrine in some ways has restricted the spread of recording, perhaps because the focus has been on the warning and on waivers. We should see recording as a substitute for Miranda and a superior safeguard for suspects.”

That’s assuming Miranda exists anymore. Rehnquist and his fellow justices may have thrown Miranda a life preserver with Dickerson. But since then, the court has gone back to its practice of wearing Miranda down to a nub.

In 2010, the court ruled in Berghuis v. Thompkins (PDF) that a suspect could implicitly waive his or her rights and that police did not have to secure an explicit waiver before beginning interrogation. In a 2012 law review article, Kamisar called Thompkins the worst thing that could have happened to Miranda short of overruling it.

“Basically the Supreme Court won’t overrule Miranda,” Maclin says, “but they also won’t extend it in ways that we might normally extend the law.”

SYMBOL AND SUBSTANCE

Leo, for his part, argues that, at this point, Miranda is more symbolic than anything else.

“Symbols matter in America,” he says. “We like things that make us feel better or safer, even if they don’t actually do anything. At this point, Miranda is mostly symbolic of how government has to respect citizens’ rights before they interrogate them.”

And those rights extend to everyone, including Eseziquiel Moreno, who became famous when he crossed paths with one Ernesto Miranda on Jan. 31, 1976.

“There’s no question that Miranda has damaged law enforcement.” —Paul Cassell. Photograph by Benjamin Hager.

The namesake for Miranda v. Arizona always had a knack for finding trouble. The arrest that led to the landmark case was hardly his first brush with the law, and it wouldn’t be his last.

In between prison stints, Miranda had tried to capitalize on his newfound notoriety by selling autographed Miranda warning cards like the ones Berliner had produced. He always made sure to carry a stack in case he needed to make a quick buck. But after a dispute during a card game turned violent, Moreno allegedly stabbed Miranda to death.

Moreno and another man were arrested, and after receiving the Miranda warnings, they clammed up and refused to confess. They were released due to lack of evidence and absconded to Mexico—never to be seen in Arizona again.

The only way Miranda’s death could have been more ironic would have been if the cops had used one of the autographed warning cards they recovered from his body to read to the man who had allegedly stabbed him to death.

But as for Miranda cards, the cops already had their own.

This article originally appeared in the August 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Think You Have the Right? The 50-year story of the Miranda warning has the twists and turns of a cop show.”