A few years ago, a retired central Ohio man decided to return to work to help his daughter pay for college. He secured employment and started the company’s training program. But three days into training, he was told the employer found a criminal record for marijuana possession from more than 15 years earlier.

He was fired.

The man contacted the Franklin County Municipal Court Self Help Resource Center, explaining that a court had sealed the marijuana record. The man was so well-organized that he still had the court entry ordering the record to be sealed. The center staff helped him write a letter to the background-check business that supplied the conviction record to his former employer. But the job was lost.

“That’s when it gets especially frustrating,” said Robby Southers, the center’s managing attorney. “There’s probably no recourse for him with that employer.”

It’s an exasperating struggle for many. A person may alert a background-check company to an error and think the mistake is resolved, but the record pops up on another background-check website. It’s an experience likened to the arcade game Whac-A-Mole for individuals who’ve had their records sealed (public access restricted) or expunged (permanently deleted).

Organizations that assist Ohioans with these issues point out that “sealed” and “expunged” records can show up on background checks, credit reports, or websites of privately owned data collection companies that proliferate across the internet.

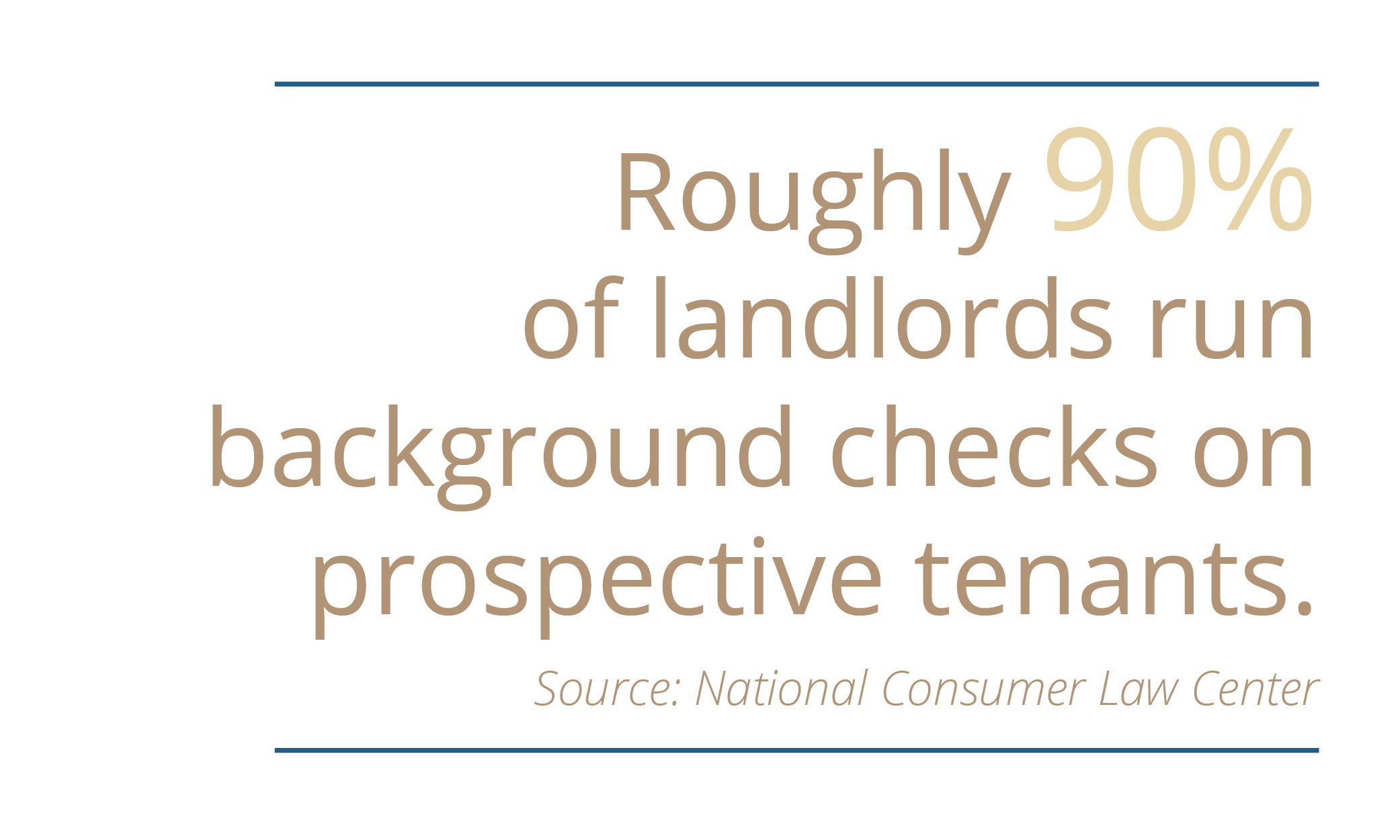

The burden falls on the individuals with sealed or expunged records to demonstrate again and again – often to potential employers or to obtain housing – that the record no longer is public and can’t be used to exclude them from important opportunities. Yet, it may be difficult for employers, rental companies, mortgage lenders, banks, or colleges to “un-know” or disregard what they’ve already learned.

“Records float out there for years before they’re taken down,” Southers said. “People have to wait until a problem comes up. It’s not ideal, but it’s what they have to do.”

Contact the Company as Initial Step

Southers notes that when a record is wrongly released, people have a difficult time understanding that courts don’t control the information appearing on commercial websites or in records sold online. While court records are kept updated, the data on a private company’s site may not reflect the most recent status of court cases.

He said the best approach to date is to write a letter to the source that released the information, alerting the business that the record was sealed or expunged and needs to be removed from the company’s database or website.

The scenario he regularly encounters involves employers. A person will finish a first round of interviews, then a problem arises. Southers notes that employers tend to wait until they’ve winnowed down the number of job candidates before paying the money to run background checks. If something negative appears on the background check, that’s when the employer often tells the candidate.

Individuals are entitled to a copy of the background check in these circumstances. By requesting it, the person knows the name of the background-check company and where to send the letter, Southers said. The Ohio Justice and Policy Center offers sample letter templates for correcting background-check information in its 2020 Criminal Records Manual that can be edited to indicate a record has been sealed or expunged.

Katherine Hollingsworth, an attorney at the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland, agrees that people need to reach out to the company or the website and ask them to correct their records.

“But there’s no easy solution,” Hollingsworth notes. “It’s a large undertaking when it involves multiple websites.”

Hollingsworth adds that commercial background-check businesses may have official forms on their websites or a phone number to call to take the first step to stop the further release of sealed or expunged court records.

Federal Law Governs Many Background-Check Screeners

Commercial background-check companies, most online, sell information from criminal records. The National Association of Professional Background Screeners, which represents employment and background screening organizations, counts 880 companies as members. These for-profit companies are regulated under the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). The companies can inform requesters about convictions, regardless of how old, but have limits on how far back they can report arrests that didn’t result in convictions. And they are barred from releasing information about sealed or expunged offenses, dismissals, or not-guilty findings.

“Twenty times a background check will be OK, then one time not,” said Sasha Naiman, deputy director of the Ohio Justice and Policy Center. “But these companies are required by law to take reasonable steps to keep accurate records.”

Although the FCRA requires background-check companies to ensure that their information is up-to-date, accurate, and complete, they aren’t legally required to update their databases at any specific frequency. Many obtain a copy of each court’s records infrequently, such as only once a year.

However, businesses that obtain bulk data from courts must follow court rules. In Ohio, that’s Rule 46 of the Rules of Superintendence for the Courts of Ohio. It states, “A person who receives a bulk distribution of information in court records for redistribution shall keep the information current and delete inaccurate, sealed, or expunged information in accordance with Sup.R. 26,” which sets requirements for management and retention of court records.

Online Companies Offer Quick, Inexpensive, Sometimes Outdated Information

Employers and landlords may decide to turn to an escalating array of online options for background checks. These online businesses provide faster or cheaper background checks than other options, said Simon DelGigante, who led the Franklin County Municipal Court Clerk’s Office’s Expungement Department, which helps people to seal or expunge records for offenses such as failure to confine an animal, violations of housing codes, and underage drinking. But the companies don’t always sell the most recent or accurate data, and many believe they don’t fall under the FCRA – or any official – oversight.

According to the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC), these companies have instituted mostly automated processes for producing background-check reports, typically purchasing data in bulk through intermediaries or obtaining it from websites through robotic web-scraping technology — and doing minimal review of the information. These practices often produce erroneous reports leading to denials of jobs and housing for consumers. Among the types of background-check errors logged in a center report:

- Mismatching the subject of the background check with another person

- Including sealed or expunged records

- Omitting information about how the case was disposed of or resolved

- Reporting misleading information, such as noting a single arrest or incident multiple times

- Misclassifying the type of offense.

“How does anyone using these companies know whether they’re getting the most up-to-date information?” DelGigante adds.

Franklin County Municipal Court Clerk Lori Tyack recommends that people secure a certified copy of the court’s order to seal or expunge a record at the time the court approves it. That way, as soon as an issue arises they can show the order to the employer or landlord, she said.

Legislature Tests Approach to Speed Process with Third Parties

Clearing sealed and expunged records from the countless websites and databases necessitates creative, affordable, and enforceable solutions that have remained elusive.

“There’s a need for a centralized and streamlined process to address this issue,” Hollingsworth said.

In 2017, state lawmakers took a swing at the issue. Under a pilot project established in state law, the Ohio attorney general chose a private company that would direct background-check screeners to remove sealed or expunged records from their databases and websites.

A report from the Attorney General’s Office to the General Assembly about the pilot noted that 205 Ohio courts sent 2,597 submissions to the company in 2018. However, the report catalogues a number of frustrations and concerns from clerks of court. The legislature repealed the program at the end of 2018.

The NCLC recommends changes to the Fair Credit Reporting Act to better protect consumers and to authorize Federal Trade Commission oversight of background-screening companies. The group also suggests the implementation of federal regulations that specify what is needed to ensure accurate information.

At the state level, the NCLC encourages state repositories, counties, courts, and other public record sources to require that companies using their data have procedures for ensuring accuracy and to audit the businesses’ practices. Also, state attorneys general should investigate background screening companies and press for reforms, if warranted, the center advises.

Commercial Sites Offer to Remove Information, for a Price

Another challenge affecting people across the country are commercial websites that offer to remove criminal records from their sites – for a fee. In late 2018, a Planet Money news reporter recounted her experience when she was arrested for speeding because she hadn’t paid an earlier speeding ticket in the same town. Six months later, she discovered that her mug shot came up first if someone did an online search for her name. She was charged $399 by the website to have them remove it. And she paid a second website to do the same.

Mug shots can spread quickly across multiple websites. About 20 states, including Ohio, have passed laws to confront this exploitation.

Ohio’s law, R.C. 2927.22, prohibits someone who publishes or disseminates “criminal record information” from asking for or accepting payment in exchange for removing, correcting, modifying, or not publishing or disseminating the information. “Criminal record information” means the photograph taken by the arresting law enforcement agency; the charges filed; or the subject individual’s name, address, or description. Not complying is a first-degree misdemeanor, and the victim can file a civil lawsuit for damages as well as attorney fees and costs.

Critics voice concerns that these laws infringe on First Amendment rights and access to public records. However, the Ohio News Media Association supported Ohio’s legislation, which the organization believed struck the right balance. The association’s executive director stated in written testimony that these websites and other outlets have taken “unfair advantage” of arrested citizens in a way that none of its news media members would. The organization viewed the law as addressing the objectionable practice, while ensuring that arrest and investigation records remain public.

Instantaneous online search results, which may pour out detailed personal information and news articles, have spurred a movement known as the “right to be forgotten.” A number of U.S. news outlets, including the Cleveland Plain Dealer, now consider requests to amend or remove articles when, for example, charges are dismissed or criminal records are sealed or expunged.

Ohio court officials note, though, that it’s not typical for criminal records themselves to show up in ordinary search engines such as Google. Searches more often generate results that point to the background-check companies where the information must be purchased.

Persistence Needed to Remove Wrongly Released Records

When letters fail to stop inaccurate, sealed, or expunged information from appearing in background checks, Southers suggests hiring an attorney as another option, although he acknowledges it may be too expensive for some people.

The frustration individuals feel elicits empathy from those trying to assist them.

“The Ohio legislature created a means for people to move on from the mistakes of their past, but the goal of record-sealing legislation is thwarted when third-party companies fail to keep accurate records,” Southers notes.

The Franklin County center tries a few other strategies to help people work around the obstacles. A social worker who has joined the staff coaches individuals on effective ways to explain their circumstances to potential landlords or employers, Southers said. The social worker also identifies short-term alternatives, such as temporary work.

The center now engages with the public through a chat feature on its website. Before the pandemic, the chat answered questions with automated responses. But now staff are assigned to directly assist those who reach out online, Southers said. He adds that this shift means they can help more people, and it particularly benefits individuals with mobility issues or who live out of state.

It seems likely that the quantity of inaccurate or no-longer-public records in background checks only will climb. The General Assembly passed three bills that took effect in April to allow more people with nonviolent criminal offenses to seal their records.

“Many clients of the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland are looking for a fresh start and struggle to make a livable wage,” Hollingsworth explains. “Sealing a criminal record can make a huge impact for that person and their family.

“When sealed criminal record information continues to appear on private websites, in outdated databases used by background-check companies, or other places online, the power of the record-sealing process is eroded.”

By Kathleen Maloney | May 2021